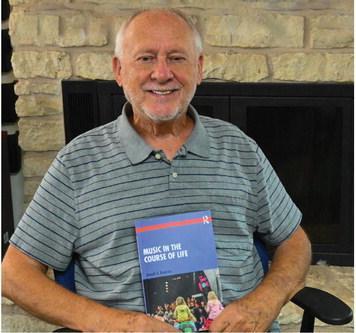

Kotarba & his ‘Music in the Course of Life’

If you are a regular at Susanna’s Kitchen Coffeehouse, the singer-songwriter performance venue in Wimberley, you might see Joe Kotarba selling tickets. He is a regular volunteer there, not just as a music lover, but as a sociologist researching the relationship between music and the experience of the self.

For four decades, Kotarba has been researching baby boomers and their music experiences. He learned that boomers didn’t outgrow the rock ‘n’ roll of their adolescence but have allowed it to inform and define the remainder of their lives and the world around them.

In his newest book, “Music in the Course of Life,” he examines how the music heard in early childhood becomes a building block for the self and how the music we listen to in later stages provides a path for our lifelong socialization. This book, writes one reviewer, “is his Magnum Opus,” that ties together his decades of research.

An accessible and fascinating read, the book’s lack of jargon, photos, and examples from his life in Woodcreek, easily draws even casual readers, through his work.

The basic concepts of the music-self he explores are the self “being there;” the self “becoming;” and the self “already been there” in terms of music.

To illustrate the self “being there” in early childhood, he writes that the music children listen to like Elmo, Sesame Street and Peppa Pig, for example, serves to help them unmerge from their caregivers and imagine themselves as a unique entity.

In later childhood and early adolescence, music becomes very physical. Kotarba cites examples of marching bands in school, mosh pits at rock concerts, and solo dancing at rave parties.

During this time, “tweens” collect ideas and experiences of who they might be from music and other sources.

He tells of a Billie Eilish concert he attended where 11 to 15 year old girls pressed up against the stage and cried, laughed and applauded their idol as she performed with green and yellow pant suit, with hair dyed green and yellow and fingernails painted in the same colors. “The girls would seem to stare at Billie from head to toe,” he wrote. “The youngest girls seemed to watch Billie, then look at themselves, to make sure their nails were appropriately green and yellow.”

In later adolescence, the self advances to the task of “becoming.” In this stage, music is used as a tool for shaping the self and not just passively assembling it. Individuals make stylistic choices and create a persona that they present to others.

As they move toward early adulthood, individuals take on new responsibilities with family, work, friends and the community. They no longer absorb music meaning and feelings from the media and their peers but start to carve a distinct self-identity. They choose music and music experiences that align with that identity.

In adulthood, Kotarba writes, individuals continue to refine the self through music to adjust to the changing expectations and conditions of aging. His research showed that “a trend among adults in American society is to generally define, expand, extend and enjoy the music genres they grew up with. Instead of seeking new styles as they did when they were young, they seek new ways to experience their favorite music.” SiriusXM, pricey tickets to performances, asking for particular DVDs as presents are examples of experiencing their favorite music.

For early elders, music is experienced as “being there” and later as “been there.”

The older one gets, the desire to explore and experiment with new styles of music and music experiences lessens as does the desire to explore and experiment with new styles of self. The desire is to simply accept what is.

Here Kotarba provides the example of Susanna’s Kitchen where, for the last 25 years, “one can hear the various styles of music associated with Americana: folk, country, the blues, old fashioned rock ‘n’ roll, and sometimes Tejano.” One of the attractions of the venue is that early elders do not have to drive through the dark and sometimes heavy traffic to attend a music event. It is comfortable, small, and inviting. In this stage, elders also seek out and attend music that reflects their religious and political beliefs, like Fourth of July concerts and church performances.

For the later elder, music is experienced as “still been there.” The self is not dependent on music as a resource for growth or development, but as enjoyment, reminiscence and awareness of life.

Towards the end of life, he writes, “music can provide the energy and meaning for compassionate interaction with older elders” and can sometimes provide therapeutic benefits. And at the very end of life, it can be meaningful for family and caregivers.

The beauty of Kotarba’s research is that he treats music as an integral part in the course of life. He shows that our appreciation for and use of music is a dynamic process that doesn’t begin when we are adolescents or end when we become adults. His work provides a much-needed explanation for the role music plays in the human experience.

Kotarba is an award-winning sociologist and a professor at Texas State University in San Marcos where he directs the Music Across the Life Course Project. Notably, he received the Helena Lopata Award for Excellence in Mentoring and the George Herbert Mead Award for Lifetime Achievement From the Society of Symbolic Interaction.

To learn more, Kotarba will talk about his new book at the Wimberley Village Library on Oct. 14, as part of the Meet the Author series. It is also available on Amazon.