Building a scene behind the curtains

When you watch a production by the Wimberley Players you likely marvel at the quality of acting by the performers on stage.

Equally marvelous is the work of dozens of volunteers who build the sets, fine tune the lighting, buy the props and paint the backgrounds.

Each play takes the work of 60 or more people working for five weeks to stage a play that runs 12 or 14 shows.

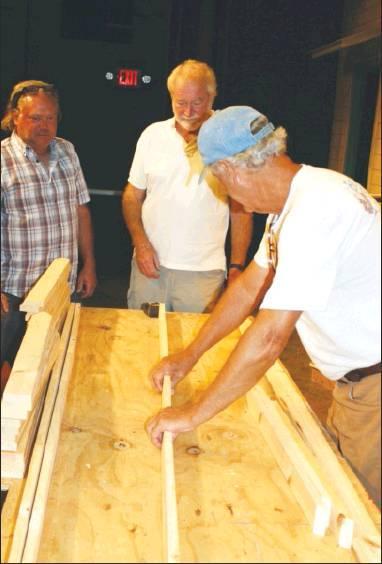

Nick Bradshaw is a retired engineer who lives in Wimberley. For the last four years he has been helping build the sets.

When you drive by the playhouse on a weekday afternoon you’ll probably see 10-12 cars parked in the lot. Those are people working behind the scenes to get the production off the ground.

“I was hanging around the house,” says Nick, “looking for something to do. My wife was telling me I had to find something to do. Then somebody said, ‘hey, they need help down at the theater.’ So here I am.”

Nick, who is also on the playhouse’s board of directors, figures he puts in more than 20 hours a week leading up to a production.

Then, when he watches a play, he spends the first hour looking at the sets to see what he missed or what he could have done better.

Gone after the show

After four or five weeks of preparation, the play runs for a month or so and then the sets are torn apart in two days. Then the whole process starts anew.

The Playhouse has six storage units filled with old props and parts of sets, but each production requires new construction.

“There’s amazing teamwork here. Someone will always help out. It’s the kind of thing that doesn’t always happen in the real world, but it does happen here.”

Nick Bradshaw, Wimberley Players

Under the watchful eye of executive producer Adam Witko, each new set is designed to fit the Wimberley stage. There’s no Internet page that shows how, for example, to build a set for a community production of “Cabaret.” Instead, the set builders call on experience, an artistic eye and ingenuity.

Nick’s favorite set was for the musical “Little Shop of Horrors.” The flower shop that’s central to the story weighed about 1,800 pounds, but, thanks to the efficient placement of 20 casters underneath, one backstage hand could turn the shop around to display either the exterior or the interior. Nick actually welded the character Audrey II, the singing, people-eating creature from outer space, that grows throughout the play. The Wimberley version of Audrey II was sold to the Angelo State University theater department for $500.

Whenever possible, pieces of previous sets are reused. The steps that were used in “Jesus Christ Superstar” were also seen in the recent production of “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas.”

The walls of various buildings are reassembled and painted play after play. The walls have to be coated with muslin fabric before they are painted to soften the look and prevent glare.

The floor gets a new coat of paint before every production. There’s a red, white and blue Lone Star on the floor now that’s left over from “Best Little Whorehouse.” That will be replaced by a green floor that looks like grass for “Picnic.”

Volunteers sit in the seats in the upper rows to make sure what goes on behind the scenes cannot be viewed by the audience.

“A lot of what we have to do is because of the lights,” explains Nick. “You never use white.”

Quick mural

The massive mural that serves as the backdrop for the upcoming play “Picnic” was hand painted by Carroll Dolezal in a few days.

Because the sets often have to shift or be moved, the construction is pretty intricate. “We have a lot of engineers who work here,” says Adam, the executive producer.

On one side of the stage is the dressing room for the actors as well as storage of various props. There are dozens of sports coats, for example, as well as boxes full of fake noses and holsters that have been used in previous productions.

When they need a prop that’s not in stock, there are a group of volunteers who scour the local thrift shops for items that will work. They may search for a framed photo that would fit in with a 1940s theme or a food container you might see in the 1960s.

On the other side of the stage is a compact work shop where the volunteers can build props such as a picket fence with a gate (which you will see in “Picnic”).

The volunteers are essential to the success of the playhouse. Sometimes a musician might get a modest stipend, but almost everyone else donates his or her time. “We couldn’t do it without the volunteers,” says Adam.

The hours some volunteers put in is staggering. Actors might rehearse for three or more hours a day, four days a week. And that’s before the shows even start. The set builders work three to four days a week.

Despite the effort, the atmosphere during set-building time is pretty laid back. There are dogs stretched out on the floor. Toddlers are toddling around. Volunteers are eating breakfast tacos. Some are glued to their computers. All to the backdrop of whining power saws and banging hammers.

Last-minute

scramble

Of course, human nature kicks in and there’s always a last-minute scramble. “Sometimes there’s wet paint when the curtains go up,” says Nick. “But there’s amazing teamwork here. Someone will always help out. It’s the kind of thing that doesn’t always happen in the real world, but it does happen here.”

The final exam of sorts is called “tech.” That happens the Saturday before the first show, lasts 12 hours and everyone involved is present. It’s when all the sets are tested, the actors prove they know their lines, the stagehands choreograph their movements and the lighting is adjusted.

Musicals, such as “Best Little Whorehouse” and “Cabaret,” are the most popular productions. Most dramas run for 12 shows while the musicals — because they are more elaborate — go for 14 shows. While most of the work is done by volunteers, there are expenses. It costs in the neighborhood of $5,000 to secure the rights to “Best Little Whorehouse” while a drama such as “Picnic” goes for around $1,300.

“The last show (“The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas”) was a sellout every night,” explains Nick. “People ask us why we don’t have more shows. Well, these people (the volunteers) have regular jobs. Plus, they are just worn out.”

Whether you are an actor with a script or a set builder with a tape measure, there’s no shortage of volunteers. When they announced auditions for the upcoming musical “Next to Normal” more than 40 people showed up to try out for six roles.

It takes four or five weeks to complete a set and only a couple days to knock it down. Most of the work and creativity is gone forever. But there’s always the next play. The show must go on.